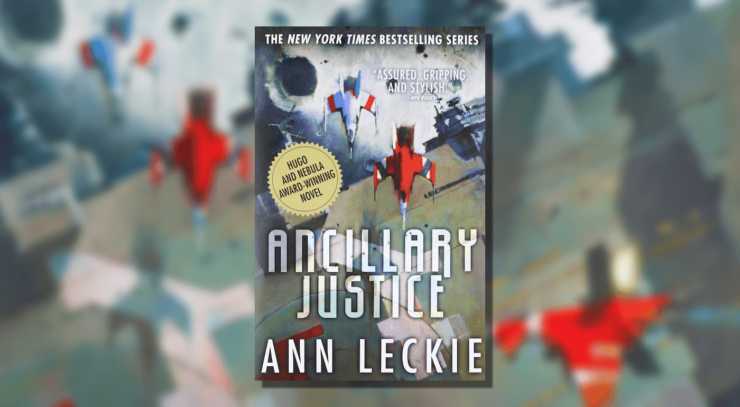

Ten years ago, Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice swept up an armload of awards and sped up the bestseller lists, buoyed by rave reviews. With her first book, Leckie recombined the DNA of a space opera into a surprising work that captured all of the gee-whiz of empires in space while at the same time interrogating what such empires were good for. Iain M. Banks, Ursula Le Guin, and C.J. Cherryh are all clear influences on the novel, as is any book about the rise and fall of the Roman Empire. The result, however, is uniquely Leckie and well worth revisiting a decade on.

Leckie hangs all of her big ideas on a propulsive story of revenge. Breq, the last remaining ancillary of the massive starship Justice of Toren, has one goal: to kill Anaander Mianaai, the ruler of the Radchaai Empire (often just referred to as the Radch). As we learn through two interwoven timelines, which span a thousand years, Mianaai is the cause of Breq’s current state and is responsible for the death of Breq’s favorite Lieutenant. Breq is sort of like John Wick with his dog, if Wick were the last remaining fragment of a spaceship’s A.I., now confined to a human body.

Leckie opens with Breq on Nilt, an unforgiving, isolated planet annexed by the Radch. Breq literally trips over Seivarden, an officer who was on the Justice of Toren centuries ago. Seivarden is nearly dead from an overdose, but rather than abandon him, Breq chooses to rescue him, even though Breq never really liked him.

In that early scene, Leckie efficiently sets up one of the key features of this world: the Radchaai language doesn’t gender people. Breq defaults to she/her pronouns for everyone unless she is speaking the language of the colonized. We only know Seivarden is a “he” because a bartender on Nilt refers to him that way. Frequently, Leckie shows Breq struggling with finding the right pronouns for the languages that require them.

In the genre today, a number of writers have engaged with gender and gendered pronouns in thoughtful and thought-provoking ways in their work. Leckie does so herself with Translation State, her new book set in the Radch world. But she’s doing something decidedly different in Ancillary Justice. Rather than pin down how a character identifies, she’s removed gender as a factor altogether. In Radch space, gender is irrelevant. All humans are “she.” As a reader, the default feminine is noticeable until it very much isn’t. It doesn’t matter to Breq, whose head we are in most of the time. In short order, it stops mattering to us, except if we stop to think about how irrelevant gender can be in many science fiction stories (though of course, it’s absolutely central to others).

What’s crucial above all else in Leckie’s story is how she explores power and the responsibility it confers on those who have it. “Power requires neither permission nor forgiveness,” Breq states, echoing Mianaai. But that’s not how Breq behaves. We see it in the early scene of Breq saving Seivarden. Breq isn’t certain why she chooses to do so—and Seivarden is a massive pain in the arse to Breq most of the time—but Leckie slowly reveals a more complex understanding of power than might always making right. It’s an aspect of the Imperial Radch series that didn’t get as much attention or spark as much discussion as the books’ approach to gender/pronouns at the time they were first published.

To spoil the plot of an almost ten-year-old trilogy, Breq as Justice of Toren does as commanded by Mianaai. Breq has no choice because the ability to decide isn’t programmed into the ship’s A.I. When Mianaai, whose sense of self has begun splintering after a millennia, orders Breq to shoot Breq’s beloved favorite Lieutenant, Breq does it. That wielding of power like a blunt weapon is ultimately what leads to Mianaai’s undoing. Breq brings Mianaai down with soft power rather than brute force. Even with the A.I.s who have been freed (by Breq’s crew) from their mandate to act only as they’re told, Breq has to use her words to convince them to support her fight, despite knowing that these powerful ships may make a different choice. The path she’s chosen isn’t the easy one.

While Breq’s larger campaign to change the Radch is what drives the plot, it’s not where the deeper nuance lies. Instead, a subtle exploration of power reveals itself in how Breq interacts with the colonized and with those that the colonized have subjugated in return. On the tea plantations in the Athoek system, for example, where the plantation owners treat their workers like serfs. Breq uses her power, without asking for permission nor forgiveness, to upset this oppressive class structure. While the results aren’t always satisfying for our protagonist, these interactions reinforce Breq’s understanding that power also comes with responsibility… which is something that Mianaai has forgotten, if she ever knew it in the first place.

Breq’s approach to building coalitions, rather than pursuing wholesale destruction, is what triggers the fault lines already built into the Radch civilization. For complicated reasons I won’t go into here the empire can no longer expand, nor can it make new ancillaries. Once those pressures start exerting themselves, those with the greatest power demonstrate all of the various ways it can be wielded, from Mianaai’s impulse to kill the non-compliant to Breq’s enlightened team building. Examining power structures is something that science fiction has long done and will continue to do far into the future, or course, but Leckie’s particular way of doing it is worth revisiting now, if only to remember how subversive parts of it seemed at the time, and how subversive other parts of it have become in the intervening years.

Adrienne Martini is a writer, an elected official, and a historic interpreter. Her most recent book is Somebody’s Gotta Do It: Why Cursing at the News Won’t Save the Nation but Your Name on a Local Ballot Can. She writes about genre books for Locus magazine.